-- Dated Jul/2011

Let’s revisit the process of learning. First a newborn learns situations like, ‘When I touch the stove, I get hurt.’ Imagine these as points in the empty space of a newborn’s mind (see Figure 1). Then they learn more situations and they begin to learn some rules like, ‘Don’t touch hot things.’ These are vectors in the space (see Figure 2).

A vector is a geometric entity that has both length and direction; think of it as an arrow. Note that when a rule

changes from ‘Don’t touch the stove,’ to ‘Don’t touch things that

make fire or turn red,’ this change is represented as the

lengthening and/or realigning of a vector.

What is knowledge?

Knowledge is all that can be learned by a mind. Therefore, knowledge is the entire set of situations, rules, and logics in the Universe. So a person’s knowledge is the complete set of situations, rules, and logics learned by their mind. Each mind has its own set of situations, rules, and logics as its knowledge set. Think of knowledge as the untapped raw material from a mine; untapped only by newborns that is. Note that the mine occupies an N-dimensional space.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-- Dated Mar/2013

Note that situations, rules, and logics are all ideas. Humans think with ideas. This means being able to notice contradictions between ideas. When someone notices a contradiction between ideas, he knows that one or both of them is wrong, and he continues by making a judgement call about which one that is. The way that we make judgment calls is by considering the contradicting ideas as rival theories -- only one of them can be right. Actually, since both of them might be wrong, we might need to brainstorm a new theory. And the way to adjudicate between the rival theories is to consider the reasons for each, and to criticize the reasons, and to criticize the criticisms. (Note that each criticism is an explanation of a flaw in an idea. Note also that noticing a flaw in an idea is a type of noticing a contradiction between two ideas.)

Learning is an iterative process of (1) noticing a problem (a situation), (2) solving that problem (making a rule for that situation), and then possibly noticing another problem in the last rule, which brings the person back to step (1). And this continues step-by-step from birth until death, from problem/situation to problem/situation to problem/situation.

Its important to note the difference between an abstract problem and a human problem. An abstract problem is like this: 2+2=?. A human problem is like this: I don't know the solution to the abstract problem, 2+2=?, and I want to know the solution. So for this example, the solution to the human problem is 'To acquire the knowledge that 2+2=4' and the solution to the abstract problem is '4'.

A problem is a conflict between two or more ideas. And its solution resolves the conflict. This is true for both abstract problems and human problems.

For example, Einstein noticed a conflict between Newton's laws and Maxwells laws. This is the abstract problem. And Einstein wanted to solve it, so this is his human problem. He solved it with his Special Theory of Relativity (it resolved the conflict between Newton's laws and Maxwells laws.)

A human problem means that a person is interested in solving an abstract problem. This raises the question: What happens to the learning process when a person is not interested in solving an abstract problem? It grinds to a halt because the person is not interested in thinking about the problem. Learning works best when the person is interested.

What are the implications on understanding each other? Answer here and here.

What are the implications on parenting and education? Answer here and here.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

While my article might not be very helpful to you, this will:

How do you think so that you come up with good ideas? What's the secret?

Choice theory.

Links to essays and dialogs about learning, parenting, education and related topics.

Join the discussion group or email comments to rombomb@gmail.com

How does learning work?

Most people learn randomly. First a child experiences a situation: I touched the stove, and I got hurt. Very soon she learns a rule to prevent such situations: Don’t touch stoves. Then she experiences similar situations and begins to improve her rule: Don’t touch things that make fire or turn red. This new rule works for more than the just situations with stoves -- it helps her in dealing with far more situations than her first rule did. So with rules, situations are easier to understand which means that with rules, situations are more easily controlled, even if one has never experienced a specific situation before.

Then she learns a logic: Beware of electric and gas lines and machines because our flesh is conductive and not flame-retardant. Notice that a logic works for more than one rule; some logics apply to only a few rules while others apply to billions or more. So with logic, rules are easier to understand which means that situations are even more controllable, rules are more easily understood, the task of determining which rules to apply in certain situations is made much simpler, and finally rules are more effortlessly applied in those situations.

But this process of learning is far too chaotic. There is far too much entropy, i.e. the amount of chaos, in this method of learning. More chaos means more possibilities for error. Consider language. The more possibilities that a statement could be interpreted into, the more ambiguous the statement is. More ambiguity equates to more error in understanding, which slows the learning process. So how do we make this less random? How do we reduce entropy in the learning process?

|

| Figure 1 |

A vector is a geometric entity that has both length and direction; think of it as an arrow. Note that when a rule

|

| Figure 2 |

make fire or turn red,’ this change is represented as the

lengthening and/or realigning of a vector.

Note that the more similar situations you learn, the more likely you are to realize that you should make a new rule, i.e. the more points you’ve learned that lie along a straight path in your 'knowledge network', the more likely you are to realize that you should put a vector along that path. If you make this realization,

then a new vector is installed along that line. Hence you’ve

learned a new rule by projecting and more importantly,

you’ll be able to tackle new similar situations that you’ve never experienced nor heard of previously.

Then the newborn learns logic as in, ‘Beware of electric and gas lines and machines because our flesh is conductive and not flame-retardant.’ This is represented by the localized superstructure of vectors (see Figure 3).

|

| Figure 3 |

learned a new rule by projecting and more importantly,

you’ll be able to tackle new similar situations that you’ve never experienced nor heard of previously.

Then the newborn learns logic as in, ‘Beware of electric and gas lines and machines because our flesh is conductive and not flame-retardant.’ This is represented by the localized superstructure of vectors (see Figure 3).

Note that the more similar rules you learn, the more likely you are to realize that you should make a new logic, i.e. the more vectors you’ve learned that are connected with each other, the more likely you are to realize that you should make a superstructure of the those vectors. If you make this realization, then a new superstructure of logic is installed along those vectors. Hence you’ve learned a new logic by projecting and more importantly, you’ll be able to tackle new similar situations and rules that you’ve never experienced nor heard of previously.

With a logic, rules and situations are less necessary to be learned because they can now be projected instantaneously, i.e. on the fly. What does it mean to be able to project rules and situations? Well most of this article is my mind's projections. I did not learn these things from a teacher, nor by reading. Instead, I learned them by projecting. The more logic one learns, the more accurately she will be able to project rules and situations, i.e. learn rules and situations without the help of teachers or even reading. So how does the mind learn logic? Or rather, how does the mind learn knowledge? First lets look at some examples of various terminology in various fields regarding knowledge.

What is knowledge?

Knowledge is all that can be learned by a mind. Therefore, knowledge is the entire set of situations, rules, and logics in the Universe. So a person’s knowledge is the complete set of situations, rules, and logics learned by their mind. Each mind has its own set of situations, rules, and logics as its knowledge set. Think of knowledge as the untapped raw material from a mine; untapped only by newborns that is. Note that the mine occupies an N-dimensional space.

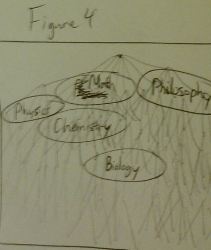

|

| Figure 4 |

- Situations are points in this space; situations are 0th order knowledge.

- Rules are the vectors that project points; rules are 1st order knowledge.

- Logics are the superstructures of the vectors; logics are 2nd order knowledge.

- The Knowledge Network is the graphical representation of all the points and vectors representing all knowledge in the universe (see Figure 4).

- A person’s knowledge set is that person’s version of the knowledge network.

- Note that all knowledge is connected either directly or indirectly to all other knowledge, i.e. all knowledge is connected. What connects it? Logics.

- It stands to reason that all logics are at least partially the same since logic is pure, i.e. it is completely void of situations and rules. Well, not all logics are void of field-specific terminology though. It seems we must define 2 types of logic.

- 2nd order knowledge containing field-specific terms is....................... Field-specific Logic

- 2nd order knowledge void of field-specific terms is................................... General Logic

- 0th, 1st, and 2nd order material of a specific field is.................. Field-specific Knowledge

- 0th, 1st, and 2nd order material irrespective of any field is........

- It stands to reason that we could interchange 0th and 1st order general knowledge with 0th and 1st order field-specific knowledge in order to postulate new knowledge in other fields; that is to say that we could interchange rules and situations from one field into those of another field while keeping the logic constant.

- Every general logic should be applied to every situation and rule in a field before dubbing that general logic as unusable for said situation or rule in said field. This is the Socratic Method, a negative process of hypothesis elimination.

- More specifically, every field-specific logic should be converted into its general form, and then systematically attempted in other situations and rules in all other fields.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-- Dated Mar/2013

Note that situations, rules, and logics are all ideas. Humans think with ideas. This means being able to notice contradictions between ideas. When someone notices a contradiction between ideas, he knows that one or both of them is wrong, and he continues by making a judgement call about which one that is. The way that we make judgment calls is by considering the contradicting ideas as rival theories -- only one of them can be right. Actually, since both of them might be wrong, we might need to brainstorm a new theory. And the way to adjudicate between the rival theories is to consider the reasons for each, and to criticize the reasons, and to criticize the criticisms. (Note that each criticism is an explanation of a flaw in an idea. Note also that noticing a flaw in an idea is a type of noticing a contradiction between two ideas.)

Learning is an iterative process of (1) noticing a problem (a situation), (2) solving that problem (making a rule for that situation), and then possibly noticing another problem in the last rule, which brings the person back to step (1). And this continues step-by-step from birth until death, from problem/situation to problem/situation to problem/situation.

Its important to note the difference between an abstract problem and a human problem. An abstract problem is like this: 2+2=?. A human problem is like this: I don't know the solution to the abstract problem, 2+2=?, and I want to know the solution. So for this example, the solution to the human problem is 'To acquire the knowledge that 2+2=4' and the solution to the abstract problem is '4'.

A problem is a conflict between two or more ideas. And its solution resolves the conflict. This is true for both abstract problems and human problems.

A human problem means that a person is interested in solving an abstract problem. This raises the question: What happens to the learning process when a person is not interested in solving an abstract problem? It grinds to a halt because the person is not interested in thinking about the problem. Learning works best when the person is interested.

What are the implications on understanding each other? Answer here and here.

What are the implications on parenting and education? Answer here and here.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

How do you think so that you come up with good ideas? What's the secret?

Choice theory.

Links to essays and dialogs about learning, parenting, education and related topics.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Join the discussion group or email comments to rombomb@gmail.com

No comments:

Post a Comment